Chimpanzees and Gorillas – 2009

Sitting on a plane wearing protective breathing masks for a ten-hour flight seemed a little bizarre.

But we were terrified of getting sick.

And for good reason. We were on our way to see the gorillas high up in the mountain forests of Rwanda and Uganda and if we had even the slightest sniffle, we would be banned from visiting them.

We were under surveillance as soon as we arrived early in the morning at a holding field for gorilla trekkers on the edge of Virunga National Park. The guides watched us closely for an hour for any signs of sneezing, coughing, or multiple visits to the washroom. Any symptoms and our day would have ended right then.

Fortunately we arrived fit and well for what proved to be a gruelling hike up steep slopes, through the damp, wet, humid forests in search of gorillas.

We had paid $500 each for a trekking permit, and had arrived at the Bwindi impenetrable forest in the Virunga Mountains right on the border of Uganda and the Congo. Only about 80 people are allowed to see the gorillas each day, and you need to book at least a year in advance. Permits have now shot up to as much as $1,500 per person in neighbouring Rwanda!

We spent the night before in a bungalow at the Mikeno Lodge, on the edge of the forest, overlooking the rift valley and the volcanos. We bunkered down to try and sleep under mosquito netting to protect us from cockroaches and all manner of flying insects. It was hard because of the anticipation of a 5 a.m. wake up call, the sheer excitement and the constant noise of the intrepid insects!

At dawn we walked a mile or so to the rendezvous point where we were eventually divided into small groups of six or seven people and assigned a guide per group. Only 50 permits are given out each day.

Each group was told about the designated family of gorillas they would be following. There were no guarantees we’d see them – visitors have actually left without seeing these magnificent creatures, though that is quite rare.

Scouts or spotters were sent ahead and had a rough idea which direction the gorillas were heading. They used radios to communicate with the guides.

And then we were off, hacking our way through the jungle. We climbed for two hours in 100 per cent humidity, dripping with sweat and struggling to keep up. The steep trails wound around tangled ropes of vines, pressing through a maze of foliage, when at last – exhausted – we found them, or they us?! In any case, there they were, nonchalantly sitting in a clearing.

Moments earlier we had to leave everything but our cameras under a tree a few hundred yards away. We had hired a porter to help carry our few possessions, mostly large bottles of water and, in truth, he also helped push us up some of the steepest, more slippery sections of the bushwhacked trail. I was running marathons at the time, but still found it exhausting and tough going in the sapping heat.

The camera lenses fogged up in the humidity, so taking photographs was challenging as we came within a few yards of ten or twelve gorillas eating, playing or resting in the clearing. Several more were in the trees.

They stopped munching for a moment to observe us and then carried on with their business. A few feet away there was a large silverback (the alpha male leader of the troop), twice the size of the young females, weighing over 400 pounds and about six feet tall. He sat on massive haunches, stripping leaves from branches. He was close enough to hold our gaze with his intelligent, liquid brown eyes.

The young gorillas displayed the curiosity of all youngsters and I sensed they wanted to inspect our shiny cameras. Their mothers, for the most part, were calm and only occasionally interfered with their offspring. They posed, played, and performed within inches of us.

But we were allowed precisely one hour with the troop. The guides are stringent about this so as not to overly disturb the gorillas.

There are fewer than 900 of the endangered mountain gorillas left in the wild and their protection and that of their habitat is an ongoing challenge.

Then we started the downhill trek through tall, tangled, scrub back to the village, a sense of having been privileged to witness something truly extraordinary.

Our drive back through Uganda was hair-raising. A white knuckle ride along roads that were nothing more than rough tracks, often tire deep in red sand – sand which invaded the entire inside of the Land Rover, including us. Back in Kigali, Rwanda, we stayed at the Hotel des Mille Collines, dubbed Hotel Rwanda – made famous by the gut wrenching movie about the genocide which ripped the nation apart a few years earlier. There were still bullet holes in the walls of the hotel. It has since been renovated.

The next day we set off in a four by four with our guide searching for an equally elusive animal – chimpanzees. This time we faced an eight hour drive to Nyungwe National Park in southwest Rwanda, right across the river from the Congo. We arrived at perhaps the most decrepit hotel we have ever stayed in but given the hardships faced by most of the locals, we counted ourselves lucky.

At four the next morning the guide woke us for our attempt to find the endangered chimpanzees. We were given a one in ten chance. But we got lucky, very lucky. Within an hour another guide flagged us down and tipped us to their whereabouts. We hiked maybe a mile into the deep African jungle, and there they were.

Actually we heard them before we saw them: screaming, whooping and making a series of excited, short cries which reverberated through the trees.

Fifteen or so chimpanzees were running in and out of shady openings, swinging through trees. When they walked it was on their knuckles. They were much harder to photograph than the gorillas because they were mostly on the move.

But every bit as awe-inspiring.

And after maybe 30 minutes observing them they were off – following the noisiest whooping we’d heard that early morning. Our guide said the alpha male was signalling to the rest of the group to follow him and they headed off, even deeper into the jungle.

Next stop on our African adventure was Windhoek, Namibia. This time our luck didn’t hold up and both our bags vanished during the multiple flights. We had a few minutes to pick up some emergency supplies before venturing deep into the sun drenched bush of Namibia’s Namib desert.

A complete contrast to the jungles we’d left behind.

The desert is home to the highest sand dunes in the world – up to 1,000 feet high. It is important to enter the national park before the sun rises – because watching it come up over the dunes has to rank as one of the greatest sights in the world. The dunes turn from inky purple to salmon to bright red.

The dancing light on Dune 45, the most photographed dune in the world, is stunning. And after photographs, it is possible to climb the dunes, often hanging on to ropes along their sharp wind carved edges.

Driving out of the desert towards Namibia’s skeleton coast we suddenly saw a truck coming towards us spewing up huge clouds of red sand. As it got closer and closer, the driver frantically waved us down. And there, in the back of his truck, our missing bags, five days into that part of the trip. We were overjoyed to see them again, in what must have been the remotest of places ever for missing baggage to be returned – at least 200 miles from the nearest airport.

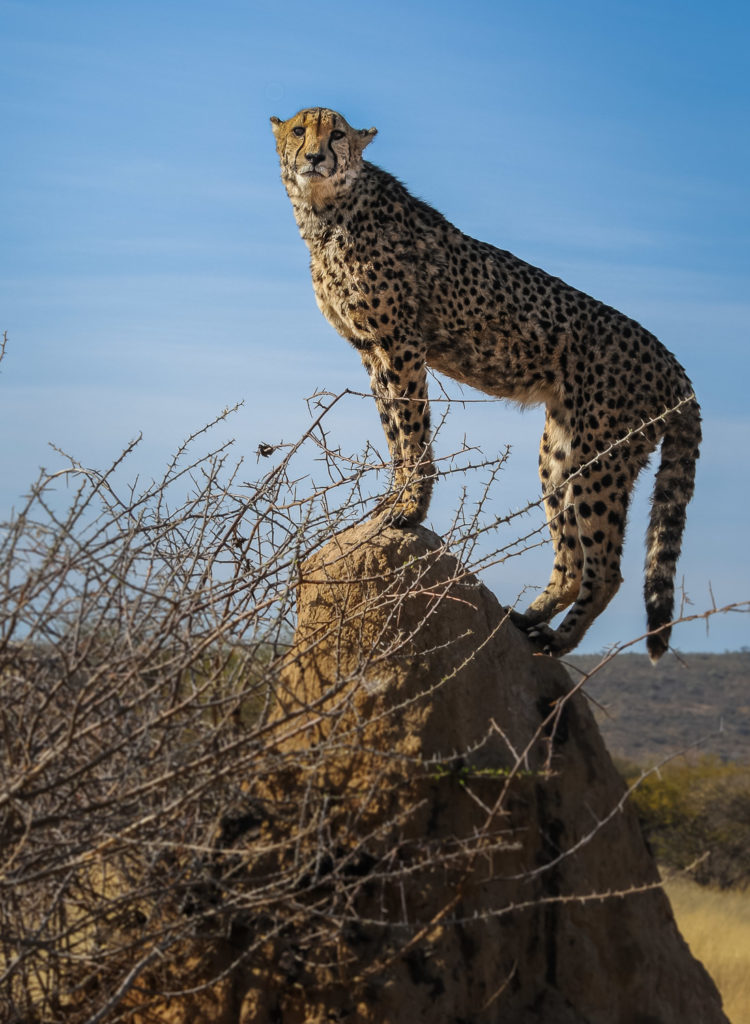

After looking at ship wreck after ship wreck on the Skelton Coast, one of the world’s most dangerous places for vessels, it was back to animals. A fantastic piece of luck was when minutes before we had to turn back, we spotted a herd of very endangered desert elephants in the fading light. We had a day at nearby AfriCats, a massive rehabilitation reserve for injured and orphaned cheetahs and leopards. So vast, that we went on a lengthy safaris to spot the animals.

We were also given a cool opportunity – to see veterinarians extract a abscessed tooth from an adult cheetah in the facility’s hospital. They made sure the animal was given huge doses of anesthetic. Its teeth were incredibly sharp.

From then on, as we wrapped up our adventure, we were on safari every day. First in Etosha National Park, Namibia, and then were drove right across the Caprivi strip, into Botswana.

One never to be forgotten night on the strip was at a river camp surrounded by hundreds of hippos, grunting all night long. They are considered the most dangerous animals in Africa, every year killing more humans than any other. But left alone they make fine, musical camping companions!!

It was our first visit to Botswana and we were based in Chobe National Park, which has now become our favourite national park on the continent because of the vast elephant herds and the huge variety of wildlife including some of the largest crocodiles we’ve ever seen.

From there we flew to the Okavango Delta to experience the Pom Pom bush camp. Remote, but far from primitive, the nine tented rooms overlook a lagoon and we experienced some our finest lion sightings of the trip.

Although we had bumped into a couple earlier in our adventure who had stayed at Pom Pom and swore they had the scary sight of a deadly black mamba snake emerging from their pit toilet, we loved every minute of our visit and learned to always “look first’!!

It was, perhaps, the most extraordinary of our African adventures.