EXPO ’67, Montreal: The beginning of a lifelong journey around the world.

“Jackson, get yourself to Rotterdam in 48 hours and there is a cargo ship that will take you to Canada,” said the heavily accented voice on the end of the phone.

It was the summer of 1967 and I was bored out of my mind, half way through the summer semester at my boarding school in the English countryside.

I had seen a program that spring on the flagship BBC news show Panorama about the opening of the World’s Fair in Montreal, Canada. It became my obsession – I wanted to see it. Actually I HAD to see it. But I had no money!

I was 16 and it was a quiet year academically between two major sets of exams so I was determined to make my dream become a reality. That May I researched shipping companies based all around Britain and wrote letters to two dozen or more of them asking if I could work my passage to Canada on one of their cargo ships later that summer.

I was 16 and it was a quiet year academically between two major sets of exams so I was determined to make my dream become a reality. That May I researched shipping companies based all around Britain and wrote letters to two dozen or more of them asking if I could work my passage to Canada on one of their cargo ships later that summer.

The idea was I would travel for nothing in return for doing manual work around the ship.

For weeks I rushed to my mail slot. But there wasn’t a single reply. So, disappointed but undaunted, I expanded my search to shipping companies around continental Europe.

And that led to the phone call a week or so later that changed my life forever. It was from an executive with a company based in Belgium describing my idea as “romantic” and said he would like to help me. But I had just 48 hours to make my way from Bristol, England, to Rotterdam in the Netherlands, to reach the ship before it crossed the Atlantic to Canada.

I had never flown before, never even been out of the United Kingdom, and I was a rather naive, unworldly, 16-year-old. Fortunately I had obtained a passport in anticipation of going to Canada.

So first I had to convince my concerned mother to let me go on this adventure and then persuade my school principal that I should forget the last six weeks of the summer term!

They both agreed. I bought a backpack and crucial supplies and booked a plane ticket to Rotterdam. My mother drove me to catch the flight. In the days before credit cards, I had exactly fifty Canadian dollars in traveller’s cheques and a few pounds sterling.

The flight was uneventful but my arrival in Rotterdam was anything but! I was given a rough location for the ship in the massive port, but the cabbie couldn’t speak a word of English. I ended up drawing a picture of a cargo ship on a piece of paper and wrote the name of it – the Eeklo – underneath my drawing. He didn’t have a clue where to find it, and stopped other cab drivers to help translate. And all the time the meter was running so fast, I was worried my few pounds, converted into Dutch guilders, would run out.

We eventually made it with less than a single guilder to spare….and I took a small row boat to take me to the 35,000 ton Eeklo anchored in the middle of Rotterdam harbour.

We eventually made it with less than a single guilder to spare….and I took a small row boat to take me to the 35,000 ton Eeklo anchored in the middle of Rotterdam harbour.

They gave me a huge welcome – in Flemish. So throughout the voyage we communicated in sign language and the little bit of English spoken by the captain. The one concession they made, with 20 sailors on board, was to give me a cabin on an upper deck near the captain – and I always ate – and drank – with the ship’s officers.

But the rest of the seven day voyage it was work, work, work. Scraping rust and peeling paint off the decks for hour after hour. What made it tough was the endless movement of the ship which made me constantly sea sick. It seemed to bounce wildly on the waves, but I was assured that the conditions in the 25 foot high waves were actually pretty calm. It is all relative!

We arrived in Quebec City and I caught a bus to Montreal where I found hostel-style accommodation in the Hotel Bonaventure, which was a new hotel not yet completed. The unfinished floors were filled with bunk beds rented out for a couple of dollars a night to students like myself.

Finally I arrived at Expo ’67. It was an amazing experience – visiting the 90 pavilions on the site from dawn to dusk. I really felt I was seeing the world, with the state of the art films and interactive displays in the pavilions. The British pavilion, which was shaped like a pyramid with the unfinished top featuring a Union Jack, made me proud.

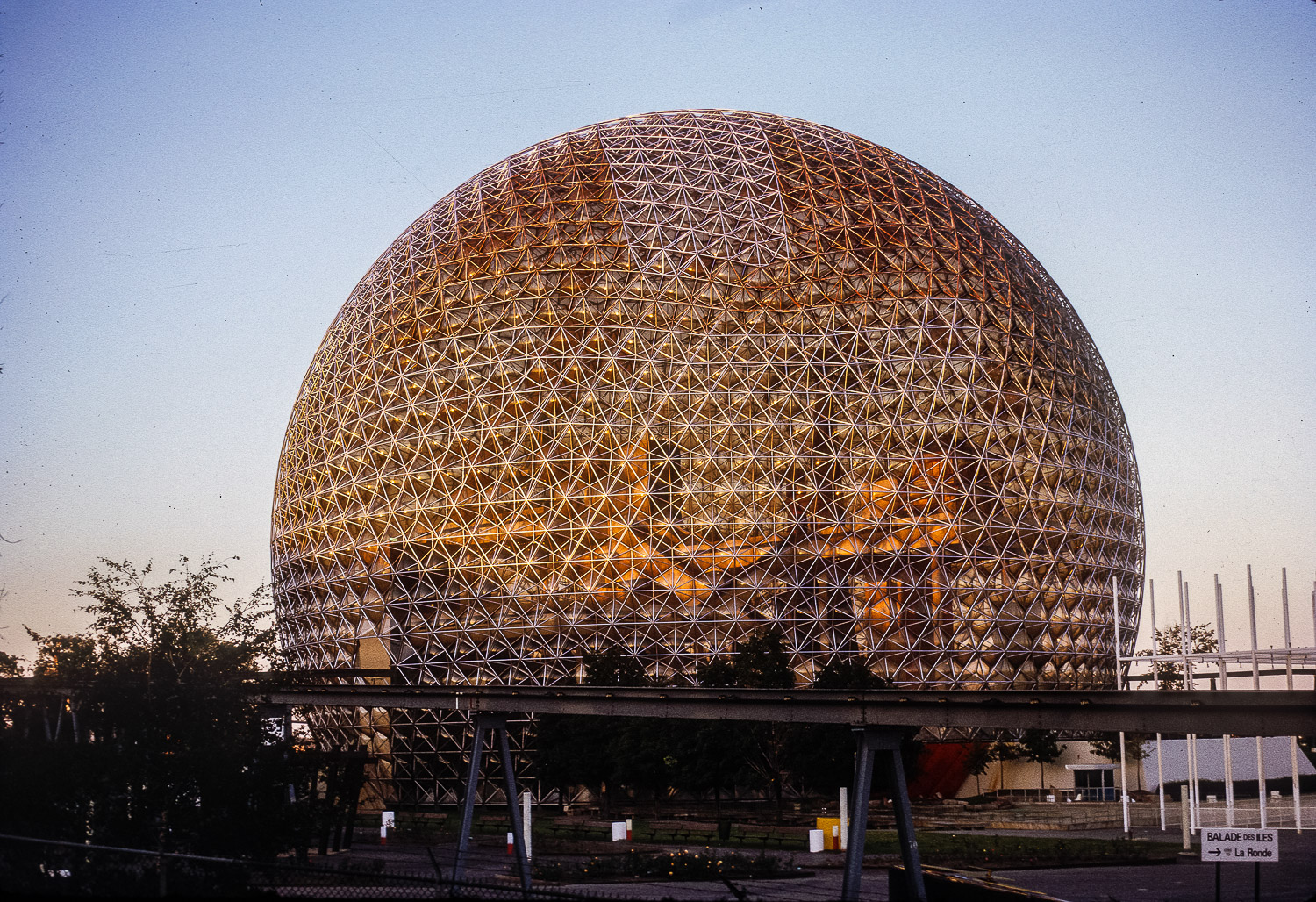

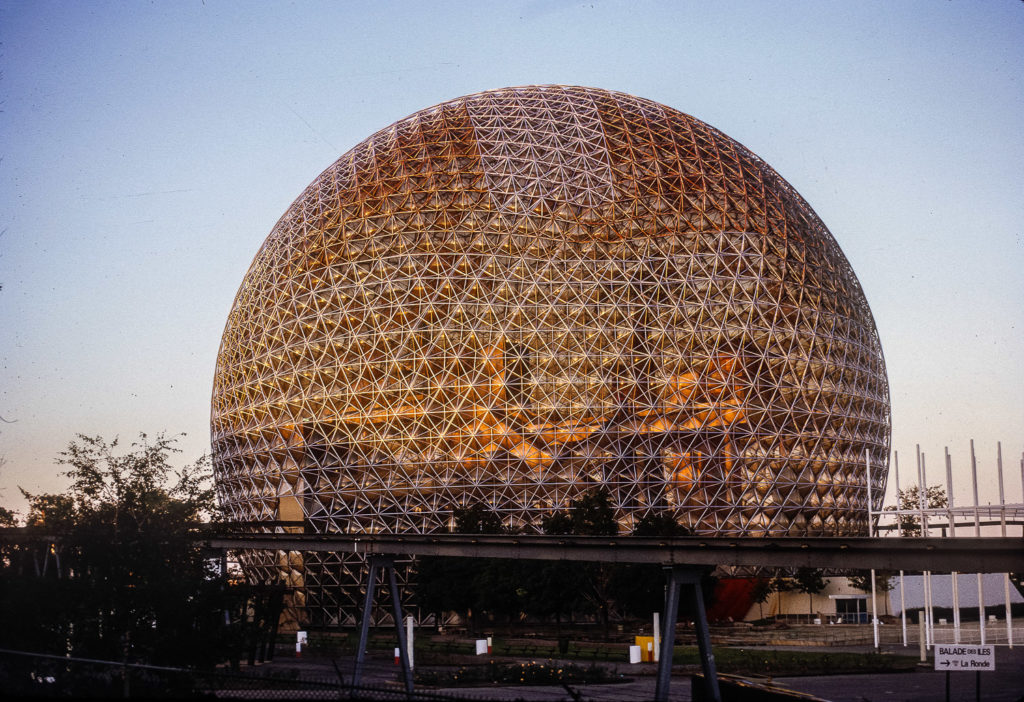

But the biggest hit was the Soviet Union pavilion, which showcased Soviet space technology and visitors could experience the sensation of space travel. The host pavilions representing Canada, and the fair’s theme – Man and His World – were stunning, as was the US pavilion with a geodesic design by Buckminster Fuller.

Then something unreal happened. I had been told to report back to the ship eight days after we docked in Quebec for the return journey to Europe. As I was walking through the crowds, often over 100,000 people a day, I bumped into one of the ship’s crew. He said he was glad to see me as he had an important message to deliver – we were sailing with our cargo of grain a day earlier the planned!

If I hadn’t bumped into him, I would have missed the return voyage. As it was, I made it back on time and returned home with enough money from my deck work on the ship to pay for my flight home from Rotterdam.

Once I got back, several newspapers and even BBC television were interested in my experience and interviewed me extensively about my adventure. That proved a life-defining experience and it led to a 50 year career in journalism. I retired in 2015.

The experience changed me forever and launched my lifetime journey. It gave me confidence and proved I could survive anywhere in the world. It was to be the first of more than 50 or more trips to every continent and both the Arctic and Antarctic.

It also gave me a deep love of Canada, where I eventually immigrated ten years later. And I’m still here, living in Vancouver.

- TC