Ethiopia: One of Africa’s Best Kept Secrets – 2019

Ethiopia is one of Africa’s best kept secrets.

When I told friends we were going there in the spring of 2019, they were almost unanimous: “Why would you want to go there….isn’t it the poorest country in Africa…..aren’t they still in the midst of a famine….is it safe?” And the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Max 8, a few weeks before we departed Canada, didn’t help.

Yes, they are poor, but proud. So proud. And while food shortages and poverty are continuing issues, they are nowhere as desperate as they once were in the Eighties. And in the ten days we were there, we never once felt remotely unsafe. Time, armed conflict and the potential for ethnic conflicts exists near the borders with Kenya, Sudan and Eritrea, so it is always best to check with for warnings before travelling.

Abiy Ahmed, the Ethiopian Prime Minister, has just been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work restarting peace talks with neighbouring Eritrea and beginning to restore freedoms in his country after decades of political and economic repression.

And as we quickly discovered, Ethiopia has extraordinary history and culture, stunning ruins, and beautiful scenery – but until now, not tourists.

That is changing. Fast.

The jewel in Ethiopia’s crown is Lalibela, an hour’s flight from Addis Ababa. The area contains 13 spectacular churches and chapels carved from solid rock beneath the earth sometime between the 12 and 13th centuries.

Some describe it as the world’s most spellbinding collection of historical religious sites. Many Ethiopians claim it is the eighth wonder of the world – there is a legitimate argument to make it one of the Seven Wonders.

As you stand on the ground above, you peer down onto the rock hewn churches, carved straight out of the massive rock at your feet. As you climb down 45 feet or more into the carved interiors, you marvel at quite how they managed such a feat.

The biggest church in this subterranean village is the 8,000 square foot Bet Medhane Alem, and its vast size creates a cathedral-like austerity.

But the most spectacular is Bet Giyorgis, carved in the form of a cross.

In addition to the 13 churches there are monasteries almost hanging from the mountainsides around Lalibela and perched on nearby mountaintops.

Ethiopia was so spectacular, in fact, that it immediately rocketed into my top five countries of all time.

In addition to its history the landscapes and scenery stand out. The Simien Mountains on the Ethiopian plateau – one of nine UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the country – are one of the most stunning panoramas in the world, with jagged peaks, deep valleys and sharp precipices dropping up to 5,000 feet.

During one driving trip around the Grand Canyon-style rim, I found myself sitting peacefully surrounded by as many as 400 Gelada baboons. I was taken to this beautiful place by local tribesmen who like everyone we met in Ethiopia were kind and gentle.

We stayed in a splendid new lodge built into a ridge on one of the rims overlooking the breathtaking beauty of the Simiens, sipping Ethiopian beer as the colours changed throughout the day.

The Limalimo Lodge is run by an English woman who is married to an Ethiopian. But the lodge was the dream of two Simien Mountain guides, who wanted to make sure local communities benefited from tourism.

It was, however, an exception to the rule. The accommodation generally has a way to go before being able to reach more luxurious Western standards, apart from Addis Ababa itself.

But Ethiopians realize the infrastructure has to change – and there are signs that it is.

Our knowledgeable guide Abenezer Dereje, said tourism grew by nearly 50 per cent last year, and will be up even more this year. It now represents nearly ten per cent of the country’s economy, and one person in 12 works for the industry.

But with 100 million people, it remains one of the poorest nations on earth. And yet the gentle people are amongst the proudest we’ve met anywhere on the planet. Never once did we feel threatened or intimidated and always felt perfectly safe and very welcome.

Dereje said that of course, everyone associates Ethiopia with the famine of the 1980s and the Live Aid concerts. It was the terrible drought and heart wrenching hunger, which inspired Bob Geldof’s Band Aid in 1984 to raise funds. But he says precautions have been taken to ensure that it never happens again.

Ethiopia is also arguably the birthplace of civilization following the relatively recent discovery of the 3.2 million year old skeleton named Lucy in the Eastern part of the country.

The actual skeleton is stored away from the public eye in an Addis Ababa vault, but there is an exact replica in the National Museum.

Ethiopia also boasts one of the longest running royal dynasties in the world, dating back to around 10BC when Sheba visited King Solomon of Israel and, as legend has it, gave birth to the country’s first king.

The imperial line lasted until 1974, when the descendants of Haile Selassie were deposed. Nowadays it is a republic.

History is well represented in Addis, an epic city of sprawling proportions. In the Holy Trinity Cathedral is is hard not to be impressed by the massive granite tombs containing Haile Selassie and his wife.

It is also home to the biggest, and most chaotic, marketplace in Africa – six square miles jammed with people buying anything that can be sold.

Outside Addis the country has medieval forts, palaces and tombs like the citadel in Gondar and the towering stone stelae of Axum. In Gondar, make time to visit the Debre Beerha Selassie Church, with beautiful biblical scenes painted onto the walls and ceilings – with gorgeous doe-eyed Ethiopian angels. The city is also studded with fairy tale castles and palaces, dating from its heyday in the 17th and 18 Centuries.

The source of the Blue Nile is close by at Lake Tana in Bahir Dar. And further south, the Lower Omo Valley is the home to the most colourful tribes on earth, including the Mursi with ceramic plates in the lower lips of the women.

For two people, including internal airfares (we had six flights) the cost was around $7,000. We travelled with Jacaranda tours, booked through Personal Travel Management based in Vancouver.

And yes, we flew with Ethiopian Airways, right after the Max-8 crash, and found the airline to be clean and efficient – every flight was on time. It is still considered one of the best airlines in Africa.

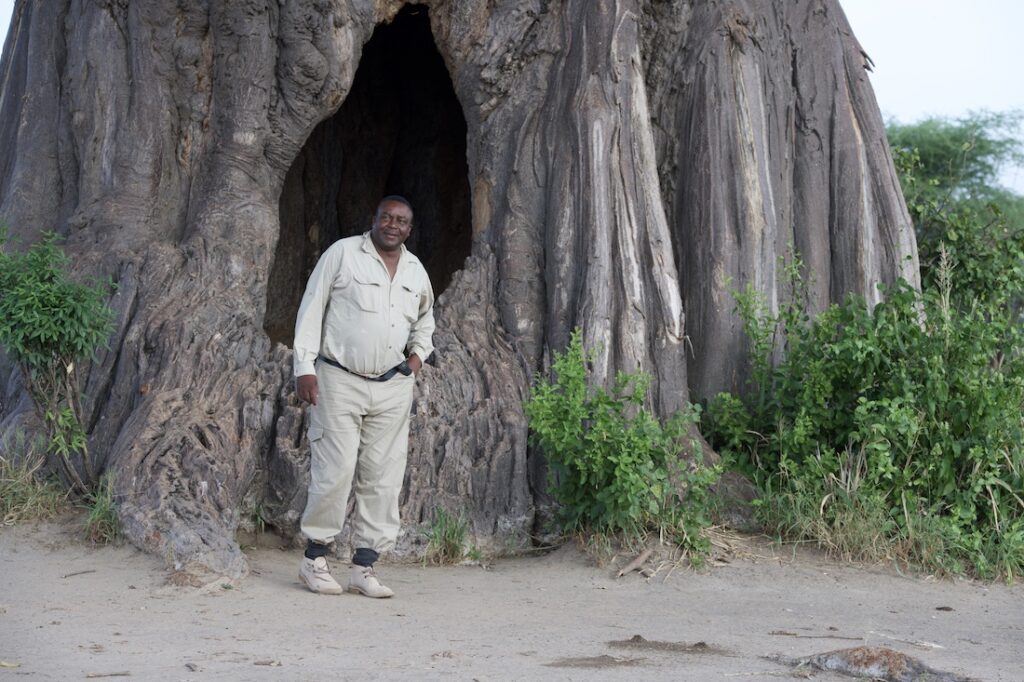

We also took a two-hour Ethiopian Airways flight as we said goodbye to Ethiopia and flew from Addis Ababa directly down to Kilimanjaro in Tanzania for the next leg of our adventure, where we were met by a familiar friend – guide John Ngoma.

Big John as he is known throughout the safari world because of his size – six foot eight inches tall and weighing in at over 250 pounds. He had guided us through Tanzania back in 2012 and we had kept in touch with him and asked him to take us on another of his extraordinary safaris.

He is revered by his fellow guides, and loved by us – and clearly all his clients lucky enough to have him. Indefatigable but also with a hawk’s eye and a walking encyclopedia of animal knowledge. I don’t ever remember him unable to answer a question.

A good guide – and John is the best – can make or break a safari and John made this one. Again. One hundred and 25 lions, 25 cheetahs and a dozen leopards over an eight day trip.

I can tell you this trip with John was the exact moment in our travelling life that we were happiest – sitting in the safari truck knowing that if there was an unusual animal sighting to be had, any animal at all, John would find it.

One day early in the trip he asked us what animals we wanted to see that day – we said cheetahs. We drove for a couple of hours right out into the Serengeti plains with no-one around. There on the horizon was a puff of dust. “There”’ said John, “that’s a cheetah”.

He drove like a crazy man the three miles to that dust funnel – and there was a female cheetah on a fresh kill with her three cubs. It was the thrill of a lifetime.

The next day, we tracked three male cheetahs as they hunted a baby impala – then played cat and mouse with it around the truck. We thought, for a moment, the impala’s life was going to be saved. But, silly thought. No. The chetahs killed her right in front of us and settled down to dine out for 15 minutes only coming up for air occasionally – blood all over their faces. Then they played and climbed al over the truck.

Tanzania is a land of raw natural beauty, with spectacular landscapes and brilliant wildlife sightings along with friendly people. It is arguably the most scenic country in Africa.

Tanzania is home to seven UNESCO World Heritage sites and forty national parks and game reserves. Because of the migration craze, the truth is that Tanzania has something to offer in every month of the year.

If the dry season produces great animal views, the wet season is perfect for birding and lower accommodation rates, suitable for keeping the budget in check. We travelled in April, low season, and in many cases had the lodges and camps to ourselves. We were lucky, too. The rains were late that year.

There is no doubt that the Serengeti National Park occupies the pole position as the most loved park in Africa, but there are many more in Tanzania which are equally iconic.

The Selous Game Reserve is famous for the large elephant herds which can be seen there. Then there is the Gombe Stream National Park where Jane Goodall studies chimpanzees.

The breathtaking sight of the cone-shaped snow peak of Mt Kilimanjaro standing 18,000 feet can either be admired from the ground or by way of a strenuous hike to the top. This dormant volcano is the highest free standing mountain in the world.

The vast grasslands of Tanzania are converted into a marching ground each year by the enmasse movement of over two million animals. The Great Migration, as it is popularly known as, symbolises the sheer will power of the large herds of wildebeest, zebra and other species, as they battle against many foes, in their quest to feed and raise their young. John has twice guided us to see parts of the migration, and it remains etched on our memories.

The fertile plains of the Ngorongoro Crater in northern Tanzania, hold such an abundance of wild animals that it has been christened as one of the Seven Wonders of the Natural World. The volcanic crater has created a unique ecosystem that is frequented by elephants and buffaloes, with their natural predators like lions, cheetahs and leopards in their constant pursuit. This largest intact volcanic caldera is undoubtedly the best place to see the Big Five in East Africa, apart from a wide range of globally threatened species.

As we said farewell to John Nkomo, and we know we’ll see him again, we made one last stop in Nairobi – at the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust’s sanctuary on the outskirts of the city.

The elephant orphanage is the most famous of the trust’s nine programs. Founded in 1977, it was the first organization in the world to successfully raise milk-dependent orphaned elephants by hand and reintegrate them back into the wild.

The trust’s CEO, Angela Sheldrick, says elephants orphaned through poaching, habitat destruction and human-wildlife conflict are picked up by rescue teams and looked after by the keepers here.

“When you take on a baby elephant it’s a long-term project,” she explains, because “their lives mirror our own.” An elephant of one year is just as vulnerable and needing of care as a human child.

“We presently have 93 elephants that are milk-dependent,” she says. “They’re with us for the first three years here in the nursery. Once they get older they need exposure to the wild herds because ultimately every elephant that we raise lives a wild life again. We just usher them through the difficult milk-dependent years.”

It takes time and patience to introduce them to living independently. Says Sheldrick: “Like your own kids, they don’t fly the nest quickly. They need to have that confidence.” The process takes up to 10 years, but the nursery’s alumni is blossoming. There are now close to 150 rehabilitated orphans, with 30 known calves of their own.

The trust was established more than 40 years ago by Angela’s mother, Daphne Sheldrick, in memory of her late husband, conservationist David Sheldrick. After Daphne died the trust has been headed up by Angela.

“When my mum was pioneering this she was the first person in the world to raise an infant elephant,” says Sheldrick. “It was difficult. One didn’t have the Internet; one didn’t have the benefit of anyone having done it before. It’s quite remarkable how far we’ve come.”

The trust’s head keeper, Edwin Lusichi, has been at the nursery for 20 years. He says working with elephants is “important and joyful and joyous, and you just feel relaxed.”

“It’s unfortunate that what is causing them to be left orphans is caused by human beings,” he adds.

“It’s our responsibility to look after our fellow creatures, for our planet and for the future. Our young ones will never get to see them if we don’t protect them now,” he says.

The Nairobi Nursery is open to the public for one hour each day, so visitors can meet the elephants and learn about the threats facing the species.

Orphans can be adopted from $50 per year and their foster “parents” can enjoy an extra visiting hour in the evening by appointment.

Lusichi is leading the tour the night we visit, introducing the 21 elephants currently on site.

The grown elephants go on to new lives in the Tsavo Conservation Area, which encompasses Kenya’s largest national park, but the bond with those who brought them up is not lost.

“They never forget the kindness and do want to return,” says Sheldrick. “The bulls less so – they travel great distances and become more independent – but the female herds are all about bonded family units. They don’t ever forget those that have raised them.”

Edwin Lusichi holds degrees in theology and computer science but has spent the last sixteen years working with orphaned youngsters. He monitors their diet, health, and general well-being until they are ready to go back into the wild.

An elephant keeper feeds a young elephant a special milk formula using coconut oil as a subsititute for elephant milk-fat.

“I came because I needed a job. But after some time it became a passion,” admits Lusichi, head keeper.He is one of thirty-odd elephant keepers who nurture a similar number of infant elephants and rhino at any given time.

Every morning Lusichi, 32, and his team don their green dust coats and khaki bucket hats, and take their young charges to browse in the thickets of Nairobi National Park, which surrounds the centre.

Elephants calves cannot live without milk during their first three years of life. The youngest orphans have to be fed a specially-blended milk formula every three hours using gigantic bottles carted around in a wheelbarrow.

As the calf’s intake of vegetation increases, the frequency of milk feeds is reduced. It took Daphne Sheldrick, who was born and raised in Kenya, almost three decades to create the perfect milk formula. She ultimately determined that coconut oil is the best substitute for elephant milk-fat.

In the evening, the elephants are escorted back to base where each one has its own sleeping stockade — sometimes the keepers stay with them overnight. “The young ones, as in under one-and-a-half years old, have keepers with them at night,” explains Lusichi.

The baby elephants are rescued from all parts of the country after having been separated from their natural families for various reasons. Under normal circumstances, young elephants live with the protection of family groups led by a matriarch. A baby elephant left alone can easily fall prey to hunters.

“Some of the babies are found fallen down wells or stuck in the mud near rivers after heavy rain and their mothers are unable rescue them. A few of them lose their mothers from natural causes such as disease, old age, or starvation,” explains Lusichi.

Kenya had an estimated 167,000 elephants in 1973 but today the numbers stand at around 30,000, which makes saving every orphaned elephant vitally important.

The young elephants are often traumatized by the separation from their families. Some of them arrive at DSWT with injuries and others look clearly downhearted. “Sometimes they are aggressive when they come and some of them refuse to eat,” says Lusichi.

As for training Lusichi says: “Elephants can tell what you think about them and can read our hearts. They will want to be with you all the time.” says Lusichi.

The keepers name each elephant under their care and learn their individual personalities. “We name them after the place that we rescue them,” says Lusichi.

Though the keepers form bonds with the elephant, they are also careful that no single elephant becomes too dependent on or attached to a single caretaker. The youngest elephants have a different keeper each night, and the staff are regularly rotated between Nairobi and the release centres in the wild.

We have adopted several elephants over the years…Kithaka being the most special. And also given adoption certificates as gifts to people all over the world.

It is a remarkable place, and brought tears to our eyes as we watched them in their mud-baths and later as they ran in from the jungle for their milk shakes.

As A.A Milne wrote: “Some people talk to animals. Not many listen though. That’s the problem.”

The good news is the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust and all the caregivers listen and act to save the orphaned elephants.